In the midst of a deep dive into the Smithsonian Folkways archive, I stumbled across an album that has quickly become a new favorite of mine. Tabla Tarang — Melody on Drums by Kamalesh Maitra is a showcase for his mastery of the tabla tarang, a collection of 10 to 16 tuned drums which allow a drummer to play the melody of a raga. Tarang means “waves”, which is apt description of the flowing sound Maitra produces by moving over the tablas in rapid, fluid motions.

AllMusic lauds the album as “perfectly executed”, but the reviewer observes that “even true aficionados… can become bored partway through the 45-minute ‘Raag Mia Ki Todi’”, the closing track of the album.

Reading this tossed off comment reminded me of an interview with Zadie Smith, where she speaks about the “classical model” of reading. In this model, the value ones gets from a piece of writing is proportional to the skill and effort one brings to it as a reader. Rather than approaching art as something one sits before passively, demanding entertainment, the reader must operate like an amateur musician…

…who sits at the piano, has a piece of music, which is the work, made by somebody they don’t know, who they probably couldn’t comprehend entirely, and they have to use their skills to play this piece of music. The greater the skill, the greater the gift that you give the artist and that the artist gives you. That’s the incredibly unfashionable idea of reading. And yet when you practice reading, and you work at a text, it can only give you what you put into it.

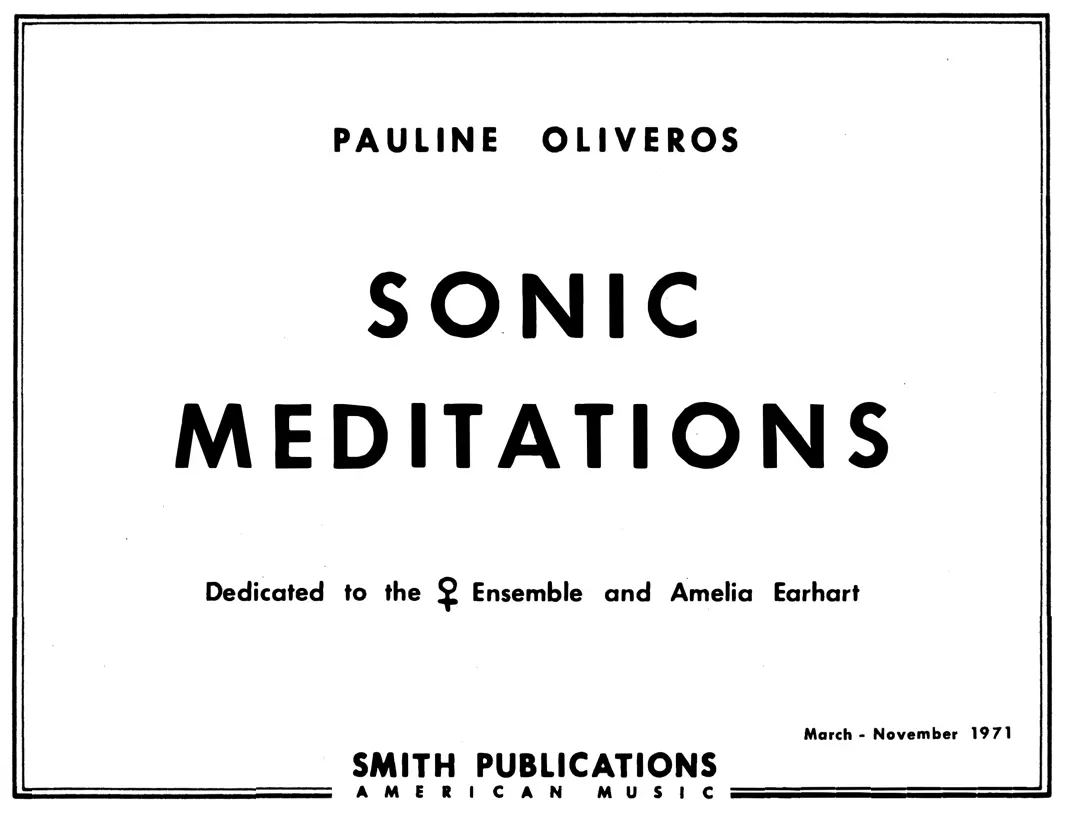

I’m also reminded of the composer and musician Pauline Oliveros, who during a period of retreat from the chaos of the late 1960s, “started singing and playing long, extended drones on her accordion, spending nearly a year on a single note, an A.” Around this same time, Oliveros began to develop a series of group exercises she called “Sonic Meditations”. These exercises were prompts for participants to practice similar forms of sustained attention. An exercise called, “Native” simply says, “Take a walk at night. Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears.”

In her introduction, Oliveros writes that “with continuous work some of the following becomes possible with Sonic Meditations: heightened states of awareness or expanded consciousness, changes in physiology and psychology from known and unknown tensions to relaxations which gradually become permanent.” She ends by writing, “Music is a welcome by-product of this activity.”

Maitra’s playing made a demand on me from the moment I heard it. It demanded that I focus only here, on this sound. The drone of a tanpura had always triggered in me a reaction along the lines of “oh great, another Indian song”. I’ve now learned to feel its central importance as the instrument which creates the tonal grounding for the elaboration of the raga. It seems to block out a space for experience where my ordinary relationship with time ceases. I’ve found myself experiencing a blurring of consciousness during extended listening to these recordings, where I feel completely within the sound. Just as Zadie Smith suggested, these experiences break the dichotomy of musician as producer and listener as consumer, suggesting the possibility of a shared state of consciousness.

Heidi Von Gunden claims that Oliveros’ music “frequently erases the divisions between performers and audiences or creators and performers”. In her essay “Where Do You Get Your Ideas From”, Ursula K. Le Guin writes, “The unread story is not a story; it is little black marks on wood pulp. The reader, reading it, makes it live: a live thing, a story.”

Attention, awareness, and attunement are all difficult activities, threatened by the constant strain on our attention. Even true aficionados can become bored by a piece of music. But the rewards of careful attention are boundless.